The fight for personal space, safety and independence

- 5 minutes to read

- 02 July 2020

- kitwan

The fight for personal space, safety and independence

In the famous TV fantasy series “Game of Thrones”, characters battle to become the heir to the Iron Throne: the seat for the king of the Seven Kingdoms.

In reality, wheelchair users have a different kind of battle. It’s not as violent as those in the fantasy series but it’s certainly something that has been frustrating many wheelchair users for long. Eventually some of them decided to take matters into their own hands – they advanced their wheelchair defense. Here’s the story of their “Game of Thorns”.

Combating unwanted touching and pushing

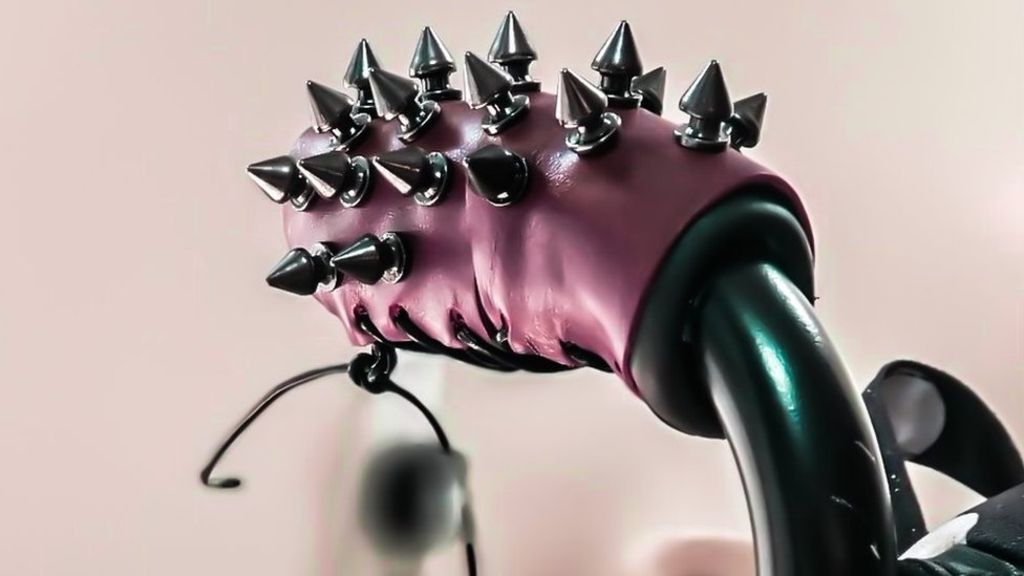

Two wheelchair users, one from Canada and another from UK, had multiple experiences of being pushed around by strangers without prior consent. Consequently, they both decided to attach spikes – modified thorns – to the handles of their wheelchairs.

The spike handles for wheelchair users to fight off unwanted pushing. (Source: www.bbc.com)

Bronwyn Berg, the Canadian wheelchair user, has installed spike handles self-made by her partner after she constantly got anxious when she heard approaching footsteps. Once a stranger grabbed Bronwyn’s wheelchair and sped down the street. The stranger kept pushing and no one came to Bronwyn’s rescue despite she screamed repeatedly for help. She feels safer now with the spikes on her wheelchair handles.

Sarah J. Waters from the UK has similar experiences, which resulted in injuries. She has hypermobility syndrome meaning that her joints can dislocate and break easily. She had two incidents in her wheelchair both with strangers pushing her without prior consent. One time her knuckles were broken, and another time her thumb was pulled open as her hand was holding the wheels when she got pushed forward unexpectedly. Like Bronwyn, Sarah decided to install spikes to defend her personal space and safety.

A serious matter of body autonomy

The spike handles got mixed reception. On the one hand, people seem to be more aware of their actions. Thus, there are much fewer manhandling situations for both Bronwyn and Sarah after they installed the handles. On the other hand, some people get offended when they see the spike handles or consider them as an act of paranoiacs.

Like many able-bodied misinterpret disability as being weak and needing help all the time, they misunderstand the purpose of the spike handles. Bronwyn clarified the handles are neither meant for hurting people, nor for stopping people to ask wheelchair users if they need help. In fact, she said people often ignored her when she asked for help.

Instead, unwanted help often goes wrong and results in her suffering both physically and psychologically. She explained further,

“Our assistive devices are a part of our body. We aren’t furniture that can be moved around.”

What Bronwyn finds crucial, which other wheelchair users would agree, is to never touch a wheelchair without permission. Like everyone with or without disabilities should do, always ask and wait for the answer before you act. Apart from the risk of injury, it is a fundamental respect for body autonomy, which is the right for everyone.

A wheelchair user taboo: touching their wheelchair without their permission. (Source: www.wikihow.com)

Results of ableism and lack of knowledge

According to a research conducted in Canada, people with a sensory or physical disability are about twice as likely to fall victim to violence than those without a disability. Another research in UK revealed that over 60% of the British public admitted feeling uncomfortable talking to people with disabilities. More communication and education on disabilities are inevitable to improve the situation.

Dr. Amy Kavanagh, a visually impaired activist, started a #JustAskDontGrab campaign in 2018 to raise awareness of acceptable approaches to help people with disabilities. As seen in the video below, people tend to just grab the arm of the person whom they’d like to help without prior consent. Many of them don’t realize that their well-intentioned help is actually very intrusive.

The campaign widely resonates with many other people with disabilities, who share on social media their experiences of being mishandled and common misconceptions about disability they noticed. For example, mobility aids like wheelchairs constantly inspire feelings of pity. The able-bodied hardly notice the independence and positive relationships people get to enjoy because of their mobility aids.

The evolution of disability culture and etiquette

Another approach for educating people about disabilities comes from Andrew Pulrang, a freelance writer with lifelong disabilities from the U.S. In a Forbes article he discussed about the disability culture of then-and-now and provided a “reimagined” guide of disability etiquette.

Andrew pointed out that people with disabilities nowadays tend to accept some ideas and behaviors more as the disability culture continues to evolve. For example, one can tell the cultural shift from the disability language style among people with disabilities. While the older generation with disabilities tends to prefer the “person first” language like “person with a disability”, the younger generation often prefers “identity first” language like “disabled person” or “I am disabled”. They consider them as statements of pride rather than negative labels.

He also shared that conventionally people with disabilities have somewhat learned to lead a positive life with disabilities and tackle ignorance with information. While all these should be practiced as a conscious choice, many tend to expect these optimistic qualities from people with disabilities.

How much do you know about disability etiquette? (Source: www.cpp.edu)

Considering the above and the influence of social media, where more open conversations are being made about disability, Andrew proposed the following reimagined guide of disability etiquette:

- It’s okay to mention or ask about a person’s disability if it’s relevant to the situation.

- Offer to help a disabled person is encouraged but one should never act against their wishes. People should listen and respect.

- Never try to lecture disabled people their way of thinking or talking about their own disability.

- Any unsolicited medical, emotional or practical advice to disabled people should be prohibited.

- Be responsible for your own management of feelings about disability and education on disability issues.

- Don’t make a futile attempt to defend the indefensible. Apologize when you make a mistake about disability and move on.

What do you think about the spike handles and the reimagined disability etiquette? How do you prevent and resolve conflicts with the able-bodied?